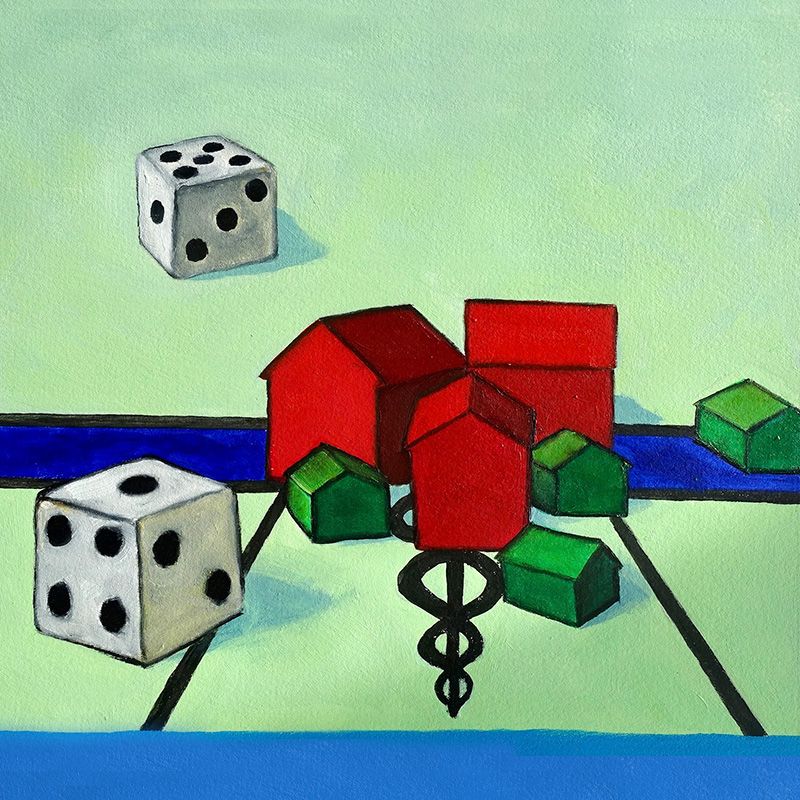

ealth care trade publications are reporting that U.S. hospital-centric health systems are in for another phase of consolidation and changes in ownership control. Why? Crashing financial performance for many are driving credit rating down drafts. Threats of receivership, out-right closures, and “shotgun weddings”; i.e., forced mergers and acquisitions have returned. Additionally, a few are reporting “full beds” with negative operating financial performance. Stop and think about any other industry that is producing and selling at capacity as it’s losing money.

cover story one

Consolidation in Health Care

Post pandemic economics

By DANIEL K. ZISMER, PhD

Two key questions loom large here. First, is this phase of health system consolidation different from all those that came before? Second, are independent physician groups necessarily swept along in the macro-economic tides that are dragging down the financial performance of growing numbers of community and academic health systems?

Looking at the first question, is the financial performance swoon simply a repeat of bygone market cycles or is it something different? Clearly, SARS CoV-2 and the Covid pandemic, caught many health systems ill-prepared to care for so many so quickly, fighting the unknown as best they could with what they had. Resources got stretched and strained. Performing more profitable elective procedures was put on hold, and health systems had to do what they could with the economics and financial effects handed to them, all to be sorted out later when the flood drained.

Think about any other industry that is producing and selling at capacity as it’s losing money.

As health systems emerged from the pandemic, they ran full face into galloping inflation and supply chain pressures. Spiking inflation rates provided labor unions the fuel for hammer and tong negotiations yielding unprecedented wage and benefits increases, which would not be matched by increases from third-party payers. Income statements and balance sheets became pressured and will be for years to come.

Then enter the more recent triple threat, Covid/flu/RSV. Again, beds fill, reimbursement rates are uncertain and profitable, elective clinical strategies are once again put on hold. The lessons learned are community health systems are constrained and hobbled by relatively fixed capital structures, inflexible mission commitment and high fixed cost operating expense structures. Moreover, many are overly dependent upon the loyalties of private, independent physicians who aren’t necessarily dependent upon community health systems or academic medical centers for their existence.

So, is the current state of economic and financial performance affairs for hospital-centric health systems the same as with past “down cycles”? The answer is yes and no. “Yes”; it is difficult when market dynamics and macro-economic shifts challenge health systems’ clinical programming and business model assumptions regarding how the world around them should work, but doesn’t. “No” community health systems could not have expected the totality of what a pandemic and the aftermath could throw at them. Those that did survive more than likely have fortress balance sheets and leadership with the permission of governance to pivot on a dime when economic market conditions require.

Independent Physician Groups

Now, on to whether independent physician groups are necessarily to be swept along in the same maelstrom of macro-economic issues as their community hospital and academic health systems counter parts. The answer is “it depends”. While it is true that independent medical groups are subject to some of the same macro-economic and market pressures as community health systems, such as downward pressures on price, utilization and total costs of care, as well as upward pressures on operating expense inflation trends and related credit risks, independent medical groups have fewer constraints on their abilities to act and react as market dynamics shift negatively under the struts that support their business models.

Clinical and business models for independent medical group practices differ from those of most hospital-centric health system models. The greater proportion of community-based health systems operate from not-for-profit, tax exempt corporate structures and are governed by community-based lay boards. Mission directions, and related strategies, are directed by these boards. Mission strategies can be directed, and mis-directed, to a wide-ranging scope of activities that consume financial resources beyond a business model’s ability keep up, such as ambitious financial commitments to serving the indigent, taking on responsibility for the health status of communities served and delivering on—and maintaining—multiple clinical service lines and programs regardless of their financial performance. Likewise, many are committed to serve all regardless of third party coverage plans, i.e., regardless of what the governmental and commercial payers agree to pay.

Academic medical centers carry the financial burdens of teaching and research, as well as the need to supply complex medical and surgical care to patients whose third party coverage may leave these institutions holding the bag for high levels of uncompensated care.

Independent medical and surgical-focused group practices have mission commitments as well. However, governance is typically controlled by the owners of the practice. They are personally at risk for the financial decisions made, as well as the business model’s abilities to perform financially. These operating medical services entities are not tax-exempt, nor are they eligible for lower rate debt financing nor special grant and research funding. Consequently, non-funded mission strategies need to be affordable, over and above meeting the compensation expectations of the providers who own the practice.

Leveraging the Value of Business Consolidation

A large proportion of community-based health systems are not, in fact controlled locally. It is more the case, these days, that they are a member of a larger system, including multi-state systems. Much of the consolidation of these systems has been driven during times of financial challenge, serial mergers of financially-challenged, smaller health systems into a larger system are not stemming from macro-economic dynamics, or state and federal driven health policy shifts.

Corporate consolidations for the purpose of “getting bigger” don’t always payoff. During challenging times, even the largest health systems are usually forced to ration capital and jettison unprofitable clinical services. With consolidations, health system boards are no longer in control of mission strategies or clinical care programming. Physician services strategies are also controlled from the headquarters. Few large scale health system consolidation strategies are ever as fruitful as advertised. The reasons are not as complex as one might be led to believe.

Acquiring companies in most industries look for “accretive transactions”; those that will be financially productive based upon changes in operations that benefit the acquirer. Consequently, history demonstrates that with each successive merger of a financially troubled health system by one larger, the financial effects are often dilutive, nor accretive. The acquirer typically is never fully aware of the risks not evident in the financial statements of each merger transaction, those such as years of under-investing by the acquired, competitive market risks, payer contracting risk, risks inherent in the potential reactions of the affiliated medical staff and achieving proposed or promised operating economies that almost never work out as planned. The reason is reducing localized costs generally requires staff reductions, and the consolidation of “back-office functions” with the corporate headquarters. Few members of local community health system governing boards that authorize their organization to “merge”, want to be responsible for the aftermath that comes with layoffs in their home town communities.

Corporate consolidations for the purpose of “getting bigger” don’t always payoff.

Independent medical groups, on the other hand, can be much more strategic and focused with consolidation strategies Such transactions are typically focused locally or even regionally. They can be like-to-like specialty focused or they may be multi-specialty by design. The integrating structures are operated more like partnerships than “take-overs”, and physicians are more likely to treat new partners as peers rather than as adversaries in a “take-over” transaction.

With most medical group integrations, size, scope and scale leverage opportunities can be baked into the plan at the front-end. The more typical consolidation strategies address keeping patient referrals “in house,” thereby minimizing the need to send patients out for necessary and profitable medical and procedural care. This achieves the required size, scope and scale to create the economics sufficient to add and control profitable ancillary services, such as imaging centers, ambulatory surgery centers, infusion therapy centers, rehabilitation services, as well as the sale of complementary retail products, for example, eye wear, pharmacy services and durable medical equipment. Other opportunities include joint payer contracting, consolidation of “back office” support services, creating an affordable shared electronic medical record and creating size, scope and scale of services sufficient to afford expansive satellite site placements.

Sufficiently-sized new facilities expansion projects attract well capitalized and experienced private medical facilities development and management firms. These firms partner with medical groups to co-design, co-capitalize, and co-manage “bespoke” specialty medical facilities—facilities designed and developed to specifically facilitate a strategy of aligned physician group partners. The larger, well-established medical facilities development firms will also manage the developed properties, the co-investment structures for the physicians partner, and will provide financial liquidity opportunities for physicians that retire out of the real estate partnership; i.e., the facilities partner will “cash out” the individual physician facilities partners who wish to retire and walk away.

Accessing Capital

Not-for-profit community hospitals, whether free-standing, or as members of larger, dispersed systems of care, typically access capital through the tax-exempt debt financing markets. Essentially, the tax-exempt debt markets are public markets. The majority of debt financings for community health systems are accessed through these markets. Tax-exempt debt is traded in public markets, much like the stock market. It is a highly regulated sector of the financial securities industry. Consequently, applications of tax-exempt debt to community health systems are highly regulated, tightly controlled and publicly reported. Community health systems with this type of debt fall under routine performance and reporting requirements. Stringent debt covenants can apply, meaning when community health system financial performance falls below covenant standards (bond ratings), the borrower’s credit rating can be lowered sending a “flashing” signal to bond holders; e.g., “dump the bonds”. The borrower operating under such conditions can be put “on watch” for long periods of time. When the credit ratings are lowered to “dangerous levels” the system runs the risk of receivership. With receivership, an external trustee steps in to take control. Typically, some form of consolidating event occurs hereafter, i.e., before the community health system fails to turnaround. Larger, better capitalized health systems are always on the prowl for failing turnaround candidates i.e., the debt owed is downgraded to a point of what is determined to be “distressed debt”; it is repriced to a fraction of its formerly listed “par value”, and the acquirer walks away with a bargain basement price on a health system ripe for a turnaround artist to step in.

Independent medical groups operate in much more expansive and less restrictive capital markets environment, including the ability to access less regulated private debt and private equity investors. The larger the practice, the more expansive are the opportunities. Bank debt is often more readily available, and medical real estate development firms will finance multiple facilities investments, as cited above. Recently, a growing number of private equity firms have emerged to acquire all or portions of medical practices. Independent medical practices with sufficient size, scope and scale can be much better positioned for the financing of various pieces and parts of their business strategies. Investors in medical practice opportunities may have little or no interest in how community hospitals are faring with their financial performance challenges. Why not? Because as sophisticated Wall Street investors often say “these two general asset classes are non-correlated”, meaning negative market conditions for one class (community hospital and health systems) does not, necessarily affect the value propositions available in another (private medical practices); the market conditions of one potential investment class doesn’t affect the other.

Closing Observations

I have often reminded governing boards of community health systems and medical practices, large and small, that while the focus of their efforts intersect at the point of patient services and care, community hospitals, academic medical centers and independent medical practices are not in the same business. Community health systems, especially the not-for-profits, are governed by community representatives charged with serving defined communities with an array of omni-available medical and health services, abiding by rules and regulations defined at federal and state levels, including by tax-exempt codes. Independent practitioners, on the other hand, operate private businesses they own, govern and control. The independent medical practice business model differs from that of the community health system and the academic health center. All should not be “lumped together” when considering market-based opportunity and risk.

Daniel K. Zismer, PhD, is professor emeritus, endowed scholar, and chair, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota. He is also co-chair and CEO, Associated Physician Partners, LLC and the co-founder of Castling Partners. dzismer@appmso.com.

MORE STORIES IN THIS ISSUE

cover story one

Consolidation in Health Care: Post pandemic economics

By DANIEL K. ZISMER, PhD

cover story two

JAK Inhibitors: A promising new drug class