Minnesota health care roundtable

The Health Care Workforce Shortage

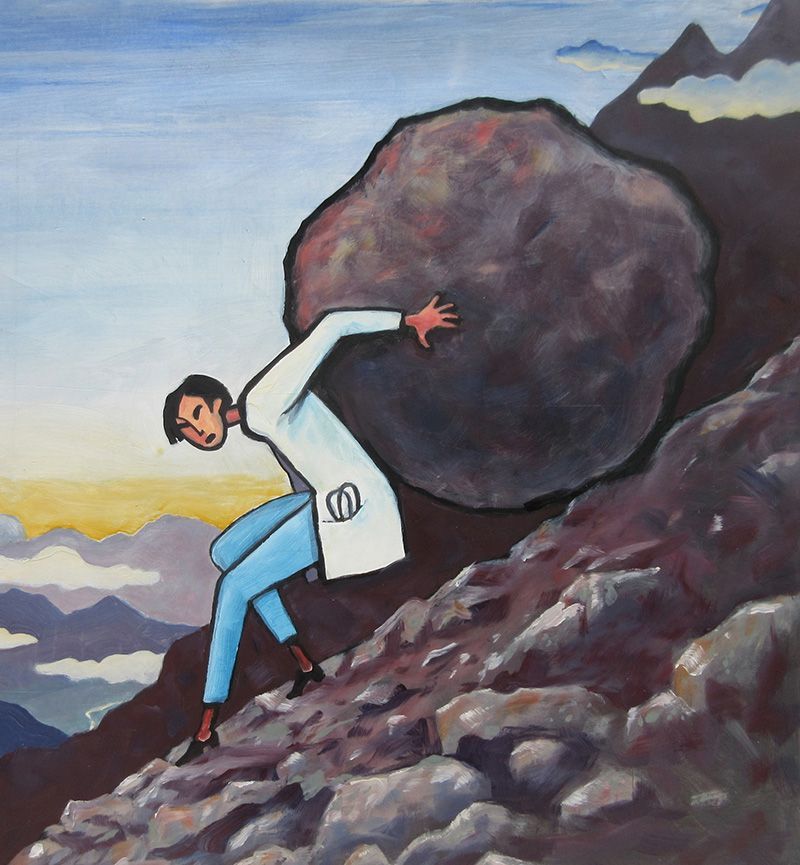

Facing a crisis

The following report from the 56th session of the Minnesota Health Care Roundtable addresses important issues surrounding the health care workforce shortage crisis. In this session we examine a growing concern that is impacting all industries nationwide. Health care is experiencing the most serious problems, in part due to the pandemic, and response has varied from hospitals laying off 100’s of staff members to offering nurses 6-figure signing bonuses. Our panel addresses these issues; their root causes and explores solutions through the specific lens of the health care industry in Minnesota. We extend our special thanks to the participants and sponsors for their commitments of time and expertise in bringing you this report. This fall we will publish the 57th session of the Minnesota Health Care Roundtable on the topic of digital transformation in health care. We welcome comments and suggestions.

What are the three biggest challenges that the health care workforce shortage poses to your organization?

Carolyn: It poses important challenges but also an important opportunity. Many individuals are interested in nursing as a first or new career. Aware of the shortage, young people see a career that will guarantee employment options for the foreseeable future. Challenges we experience as one of the academic institutions preparing the future nursing workforce for Minnesota include faculty and preceptor shortages, as well as a related inability to adequately expand our class cohort sizes to meet the demands of prospective nurses.

Tenbit: It results in limited access to health care for our members, particularly in greater Minnesota and in communities where people of color live and seek care. We are concerned about access to mental health, primary care and specialty care for our members throughout the state. Due to factors such as the demanding nature of health care jobs, concerns for one’s health and safety and the alarming rate of burnout among health care workers, a sizable portion of the workforce has exited the field. This has been further exacerbated by the pandemic; we simply don’t have enough physicians, nurses and other allied health professionals to meet the needs of our members. Hospitals are closing some or all services in rural communities, and this is further adding to the already existing health inequities.

Workforce shortage, growing labor cost and the pressure to increase provider reimbursement are all intertwined realities of the health insurance industry. According to the Advisory Board, median labor expense for health systems per adjusted discharge has risen by 45% from 2019 to 2022 while patient volume is almost at the pre-pandemic level with an increased acuity. The increased acuity combined with an equally challenging shortage of post-acute care beds has significantly increased length of stay for hospitals further reducing the already low profit margins. Increase in expenses and reduction in revenue are making some health systems long-term viability questionable. In turn, there has been an increased pressure from health systems to raise reimbursement. The significant workforce shortage is an issue most health systems are facing and must solve for in real-time. This doesn’t leave much flexibility to explore innovative reimbursement models and value-based agreements prioritizing value of care over volume of care. In some cases, health systems are walking away from risk-based agreements given their dire financial situations.

JP: During COVID, governmental public health workers who had worked in their organization for five years or less were far more likely to quit and change organizations compared to their peers. We have to figure out how to retain these staff going forward if we are going to stem the tide of turnover. Prior to COVID, state and local governmental public health had lost over 15 percent of its workforce since the Great Recession. It had also been hit by the onset of the “silver tsunami”, the generational retirement associated with Baby Boomers starting to age out of the workforce. Policy and demographics together are powerful and not unique to public health. However, another issue is unique to public health— it competes with health care, arguably the best paying industry, and has all the weakness of the public sector, such as slow to hire, offering relatively less pay and bureaucracy associated with promotions. This has made it difficult to hire and more difficult still to retain during a time when the private sector is competing hard for talent.

Rahul: Care capacity. Our members rely on their staff to carry out their missions of serving their patients and surrounding areas. Without a robust workforce, the capacity to care for our communities is threatened. Staffing shortages throughout the health care sector have both immediate and multiplying effects. Staffing shortages make it hard to coordinate care for patients. Another issue is reliance on outside talent. Hospitals and health systems have had to rely on staffing agencies to bring in traveling staff to alleviate the staffing shortages. While it helps immediate care capacity issues, it can significantly strain long-term financials as these contracted employees cost exponentially more than permanent staff. Also, there are financial considerations. Labor expenses grew by an average of 7.4 percent in 2022. It is not only the reliance on outside talent using expensive travel agency contracts that is causing labor expenses to grow. To recruit and retain the workforce, we must appropriately compensate our workforce. As with many industries, contracts are growing, and to stay competitive, our hospitals and health systems must offer attractive packages. Labor expenses are not the only costs that are rising. Non-labor costs grew by an average of 9.5 percent in 2022. Inflation is making it difficult for our hospitals and health systems to manage their funds effectively. The discharge gridlock costs hospitals and health systems $37 million a week. Minneosta Hospital Association (MHA) found that in one week of December 2022, nearly 2,000 patients were eligible for transfer to a continuing-care setting, such as a nursing home, group home or residential mental health treatment facility, but could not be discharged from inpatient care due to a lack of capacity in post-acute care settings. This resulted in 14,622 extra hospital patient days—a data sample reflecting the recent patient census situation in rural and urban hospitals.

While those are the largest three challenges to our workforce shortage, it is evident how interconnected they are and the many issues within each challenge as well.

Lynda: As the most diversified and only health care products company dedicated to maintaining a portfolio that represents its strong pharmaceutical and medtech capabilities, Johnson & Johnson depends on the health care workforce to enable our products to reach patients in need. In addition, we aspire to help eradicate racial and social injustice as a public health threat by eliminating health inequities for people of color, and we believe that a robust, thriving health care workforce is vital to supporting safe, high-quality, equitable health care. Finally, guided by our Credo as a company that has championed and supported the nursing workforce for over 125 years, as we recognize that nurses are the backbone of health care, we believe that a nursing shortage, also deemed a nursing “crisis,” is really a health care crisis for us all. Nurses provide hands-on patient care, help improve access to care, prescribe and administer medications, support and provide education and coordinate services in virtually every corner of every community. They are sometimes a patient’s only access point to health care. For health care to work, it takes a robust, diverse nursing workforce supported and empowered to thrive.

JAKUB:

As health care educators, we are challenged to identify and recruit the number of qualified students needed to address the workforce shortage, to make education and training affordable for these students; and to ensure we train students to be workforce-ready in a wide range of settings across the State.

The impact of nurses in health care is undervalued and their expertise is underutilized.

—Lynda Benton

How are you addressing these challenges?

Jakub: We have well-established and growing pipeline programs that introduce younger students to the health care and science professions. For example, we have programs out of Duluth that recruit and support students from kindergarten through graduate school. The Ladder program in North Minneapolis recruits health professionals to come into the community and mentor students, giving them exposure to successful adult role models, as well as to science and health. All of our health professional schools have active recruitment programs throughout the State. The University has focused on moderating and stabilizing tuition, and we offer a range of support from non-resident tuition waiver scholarships to full-tuition scholarships, as well as half-tuition and donor scholarships. We know that health systems are in need of health professionals who are not only skilled, but ready for team-based practice. Our training has opportunities for interprofessional learning and experience that helps build that readiness. Since there is a particular need for physicians in rural communities, and data show that doctors often end up practicing where they train, the University has programs to train physicians in smaller communities across the state. For 50 years, the Rural Physician Associate Program has paired medical students with experienced physicians in rural Minnesota. Sometimes these physicians end up training the doctors who will replace them when they retire. We are working to expand training opportunities in rural communities across the State, building on successful programs like the one in Duluth and developing new partnerships as with CentraCare in St. Cloud.

Lynda: We are continuing our rich history of championing and supporting the nursing profession in three important ways. We know that even now, nurses are undervalued for their impact on health care, so we are advocating and elevating awareness of the fundamental value of nurses in health care through research, advertising, external conference presence, our SEE YOU NOW podcast and storytelling. Second, we are taking action to address fundamental workplace culture and environment challenges that have led to escalating nursing burnout, turnover and vacancy rates, by working to help redefine the workplace culture and environment where nurses can thrive. We support a nurse innovation health system fellowship through Penn Nursing and Wharton Executive Education and through NurseHack4Health hackathons and pitchathons to help nurses define and power-up their innovative ideas to improve health care and bring them forward. Through the Johnson & Johnson Foundation, we are supporting mental health and well-being resources and leadership skill development programs led by SIGMA and the American Organization for Nursing Leadership (AONL), as well as researching new care delivery models for health systems by supporting the work of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Lastly, we are working to diversify the nursing profession to better reflect the communities it cares for, as well as strengthening readiness to practice through various nursing scholarships, mentorship/leadership support, continuing education and career resources like nursing.jnj.com.

Rahul: Addressing the workforce shortage is one of MHA’s top areas of focus. We are working with our members on solutions to retain the employees we have, as well as to recruit our health care workforce for the future. We just hosted our Inaugural Workforce Innovation Conference, where we convened members to learn from each other’s successes and share ideas for recruitment and retention. MHA developed a workforce road map, which is an interactive assessment to help our members identify new strategies for workforce development, connect to resources that will help adopt these strategies and serve as a guide to have meaningful and structured conversations. The Summer Health Care Internship Program (SHCIP) is a program administered by the Minnesota Hospital Association on behalf of the Minnesota Department of Health. The program brings students and employers together to give students experience in a health care environment during the summer months. In 2022, the SHCIP provided 130 plus students with over 45,000 hours of internship experience in 66 hospitals, clinics and long-term care organizations. As for the financial difficulties facing our nonprofit hospitals and health systems within the State, we must secure immediate financial support from the state legislature. Hospitals and health systems are being nimble and creative with their funds, but all options, other than cutting services or shuttering doors, have been exhausted. We are also advocating within the legislature on several workforce pipeline bills combating harmful legislation that would create additional strain on the health care workforce.

Tenbit: Burnout, turnover, workforce shortage, intense competition for recruitment and rising labor costs are today’s reality for most health care organizations, resulting in limited access for our members. UCare financially supports several provider partner organizations in different ways. For example, we provide funding for Wilder Foundation and Alluma to train mental health professionals in both urban and rural Minnesota to become independently licensed. UCare has also provided financial support to NUWAY, a substance use disorder provider with a program committed to training and supervising licensed alcohol and drug counselors from diverse backgrounds. UCare is partnering with the Minnesota Hospital Association to develop a roadmap and toolkit for health care workforce development. We have also provided year-end funding in 2022 to struggling provider systems that serve a large roster of UCare members.

JP:

At the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, I direct the Center for Public Health Systems. Our charge is to support local, state and federal public health partners in the delivery of governmental public health services and activities. About half of what we do is provide technical assistance to these health departments—helping them conduct workforce needs assessments, create workforce development plans, etc. We are also the national lead for the Consortium for Workforce Research in Public Health (CWORPH), which hosts the nationally funded Public Health Workforce Research Center, a jointly funded project from the Health Resources and Services Administration and CDC. Every year, CWORPH members and partners conduct at least eight research projects on matters of national importance to the public health workforce, many identifying evidence-based solutions or interventions around issues related to recruitment, retention, succession-planning and the like. A substantial part of the work that needs to be done in this space related to cost might also be termed “public health modernization,” essentially understanding where public health systems currently are with respect to delivering a core set of public health services relative to where they should be. That “gap” is measurable, fillable and needs staffing and funding.

Carolyn: We are working with other schools of nursing and clinical and community partners to identify solutions that alleviate some of these challenges. The University of Minnesota is collaborating with Minnesota State to reimagine nursing education and address the nursing workforce shortage across Minnesota. Our School of Nursing obtained federal funding to support the strengthening and expanding of our nursing workforce. For example, I lead our HRSA-funded RE Lab initiative (relab.umn.edu), which works with forensic nurses, mentors/preceptors and nurse leaders to encourage trauma stewardship, sustainable work strategies and resilience through intentional competency building—a unique peer and small group mentorship program—and a new nurse residency program established in partnership with the Regions SANE program. Another federally funded program specifically supports Native American nursing students pursuing advanced practice nursing degrees with similar peer mentorship and cultural connection support. Both programs offer financial support for advanced education and have potential to positively influence our nursing workforce pipeline and nursing retention.

How could the Minnesota Legislature help address these challenges?

Lynda: Minnesota has taken some important steps toward addressing challenges facing the health care workforce, including the nursing profession, through funding and legislation such as the Health Professional Education Loan Forgiveness Program, which provides health professionals and those in training with assistance in exchange for providing care in an underserved area. In addition, a law passed in 2015 requires hospitals to implement workplace violence prevention programs to ensure a safer working environment. The Minnesota Department of Health is working to address mental health needs by creating a website of mental health and resiliency tools for health care workers.

Johnson & Johnson supports the continued efforts of policymakers in Minnesota and across the U.S. to address health care workforce challenges. First, we support funding for pathway and clinical training programs, loan repayment and incentives, mentorship programs, and partnerships with community colleges. We also encourage efforts to increase educational opportunities that will enhance care in underserved areas, including support for nursing faculty and preceptors, and improving access to graduate nurses. Second, we support efforts to combat workplace violence through innovative prevention programs that address the needs of health care professionals, developing programs centered on de-escalation and staff training. Finally, we support adoption and robust funding for wellness programs and initiatives to ensure clinicians can freely seek mental health treatment and services without fear of professional repercussions or career setbacks. The Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation has created clear guidance for hospitals and care facilities to ensure that licensing and credentialing applications are free of intrusive mental health questions.

JP: The Minnesota Legislature plays an incredibly important role in the governmental public health system in Minnesota. The health of our residents and citizenry is supported in large and small ways by the investments of the Legislature. In the space of public health, one such investment relates to the Local Public Health Grant, which funds all manner of chronic disease prevention and promotion at the local level. Recently, the Legislature has also created a special $6 million fund for public health infrastructure and is considering more investment in this space, to ‘modernize’ public health in Minnesota. I lived and worked in the State of Maryland for the better part of a decade, and part of that time, I was working for the Maryland Department of Health. A lot of our inspiration for programs, especially around quality improvement, came from what Minnesota had done. It took me leaving Minnesota to realize just how far ahead of the curve it had been. But while Minnesota had previously been a ‘best in class’ funder of governmental public health in the 1990s, that investment stagnated and waned in the 2000s and has further declined after accounting for inflation since the Great Recession. This has been an issue for state public health funding, and especially local public health funding. Other states, including Oregon and Washington, have reinvested in recent years, and the issue is now in front of the Minnesota Legislature. We are pretty far behind at this point.

Jakub:

The University is the State’s partner in training health professionals to address the growing statewide shortage of caregivers. In addition to education, we work on developing new care models to extend the reach of providers’ skills, for example through telehealth. The Minnesota Legislature could support the University and other educational institutions by providing funding to help increase the number of professionals we can train each year. This means investment in more facilities, more instructional and support staff, and more student support. The Minnesota Legislature could fund programs to attract health care professionals to practice in rural and underserved areas across the state. This could help offset education costs, as well as ease the recruitment and retention issues that Minnesota’s small towns and rural communities are facing.

We simply don’t have enough physicians, nurses, and other allied health professionals to meet the needs.

—Tenbit Emiru

Rahul: Expand current programs such as the Health Care Loan Forgiveness program, the Dual-Training Pipeline, and the Summer Health Care Internship Program. Establish a one-time program for students newly enrolled in an accredited allied health technician program, supporting students pursuing a career as a medical laboratory professional, respiratory therapist, radiology technician, or surgical technician. Accelerate entry into the professional workforce by simplifying administrative processes at the health care licensing boards. Increase Medicaid reimbursement to better support patient care. The number of patients on government insurance programs continues to grow, now amounting to 61 percent of the average hospital’s payer mix. MHA urges the legislature to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates to accurately reflect the current care cost. Alleviate the care capacity crisis across the health care system. There are a significant number of patients with discharge delays from acute care hospitals. Hospitals and health systems are not reimbursed for patients’ ongoing “boarding” and cannot use those beds for new patients in need of acute care. MHA supports additional resources and incentives for hospital decompression sites.

Carolyn: Anything the legislature does that supports the health and well-being of our entire health care workforce, including nurses, will directly and indirectly help with the challenges we have along the continuum of nursing, from where we do our nursing --- in prevention, at the bedside, in the classroom, to the stage we are in our nursing journey --- the brand new nursing assistant to the established faculty member. The governor’s initiative covering the costs of training and tuition for those interested in joining high-need professions, including nursing, is a significant resource that needs to be expanded, marketed, and sustained. Those who could benefit the most from these amazing resources are not necessarily hearing about them, or being provided supplemental support, such as transportation and child care, to access the training. I also wonder about eligibility and how we might expand these programs to be available to newcomers to Minnesota. Further, while amazing resources support those entering the nursing profession via a variety of pathways, there remains a need for financial investment in those we rely on as preceptors for our future nursing workforce. They often volunteer, or are voluntold, which adds substantial responsibilities to their workload. The moral obligation mantra of “investment in those who follow you” has expected nurses in practice to not say no to these educational needs. But this is not the way many preceptors in other disciplines are compensated/acknowledged for their efforts, it is not morally or ethically okay, it is not role-modeling balance, and it is not a sustainable model in our post-covid nursing shortage and burnout environment. We need preceptors. We need to recognize this and offer solutions that are good for them, good for their clinical systems, good for the learners, and good for academia. I welcome legislative efforts that help us find those solutions.

Tenbit: Supporting lower cost educational options and technical training programs in the healthcare field, particularly for those in underserved communities. Easing the burden of requirements for documentation in Electronic Health Record (EHR) for providers.

How could the health insurance industry help address workforce shortage issues?

Rahul: Currently, over 60 percent of hospital patients are on Medicare or Medicaid. These plans reimburse hospitals well below the actual cost of care. The math just does not add up to being anything tenable for hospitals and health systems. On average, Medicare reimburses hospitals 20 percent below cost, leaving a $1.6 billion gap statewide. Medicaid reimburses hospitals an estimated 27 percent below cost, leaving an $868 million gap statewide. Commercial insurance contracts also have negotiated limits that constrain revenue growth, and they are moving away from this cross-subsidization. In our move toward value-based and accountable care, Minnesota has many innovative payer-provider relationships because finance and delivery need to work hand in hand because of the financial burden on hospitals.

Medicaid reimburses hospitals an estimated 27% below cost.

—Rahul Koranne

Lynda: As payor mixes trend toward lower reimbursement, hospitals are not getting sustainable reimbursement, which trickles down to the workforce, who must do more with less. The burden of the constriction is put on those caring for patients.

Jakub: We need systems that allow our skilled health care professionals to focus on giving care, rather than completing paperwork. By selecting and streamlining reporting requirements and supporting care models that keep staff working within their skills, it could improve burnout and increase the available number of patient contact hours.

How can workplace dynamics be changed to address workforce shortage issues?

Tenbit: Redesigning workflows to allow professionals to work at the top of their license is a must. There are many duties that can be done by non-clinical people that currently fall under the responsibilities of the providers,. Removing non-clinical work from clinicians’ responsibility will not only address one cause of burnout, it will also lead to efficiency and job satisfaction. In addition, providing flexibility of work schedules such as starting late or early and working part-time to accommodate family responsibilities are pluses.

Jakub: Prominent issues we see are the desire for more work flexibility and the need for care models that allow care duties to be delegated to the appropriate health professional. People want to perform to their highest capabilities and license. For example, in Minnesota we have nurses leading, delivering and coordinating care. They are treating chronic conditions, diagnosing common problems and educating patients. Similarly, Minnesota pharmacists are practicing at an advanced level to manage medication under collaborative practice agreements with physicians and nurse practitioners. Having these non-physician health care professionals practice more autonomously has shown us a way to reduce health care costs, improve outcomes and provider satisfaction, and ameliorate the growing shortage of primary care providers.

Lynda:

Even today, the impact of nurses in health care is undervalued and their expertise is under- utilized. We need to replace transactional language like needing to “recruit and retain” members of the nursing profession, and replace it with working together to attract and strengthen an innovative, thriving and diverse workforce. To do this, we need to redesign workplace cultures and environments where nurses are truly valued for their insights and expertise. Nurses deserve a safe work environment where they can provide high-quality patient care, where their ideas are sought out, listened to, and supported, where they can work flexible schedules, where they are fairly compensated, where they can devote more time to patient needs, as opposed to non-clinical tasks or extraneous administrative burdens, where they can continue to grow and flourish in career paths of their choice and where their mental health and well-being is supported. Nurses, like any other profession, are looking for workplace cultures that recognize and value their expertise and actively seek their input on problem areas and ways to improve them. Nurses want to be visible, valued, and heard.

JP: Pay is often highlighted as the reason people leave jobs. That’s partially true: it is often the first reason considered, but it’s not the only reason. People leave jobs because the pay is not good, or they can get paid more elsewhere, but they mostly leave because they don’t like their boss, or they don’t see an internal trajectory that makes sense, or they’re not engaged. That’s true in public health just like that’s true in health care, just like that’s true in government or anywhere else. Sometimes it’s difficult to pay people more or to increase pay bands even on the most in-demand jobs. While that’s an important thing to do, to recruit and retain the best talent, no question, folks get stuck on that too much. There’s a lot that can be done to improve the workplace culture if you are an executive or mid-level manager. Research consistently shows that increasing perceptions around organizational support and employee engagement are within the sphere of control of managers and supervisors - and these really lead to increased job satisfaction and retention. Retention is about pay, but not just pay.

Rahul: Minnesota hospitals and health systems are also extremely committed to health care professionals as they are critical care team members who care for our patients. We do so by offering nation-leading compensation. Adjusted for cost of living, Minnesota ranks 2nd in the nation for compensation for nurses and in the top 30 percent for physicians nationwide. We provide flexible scheduling- over 57 percent of nurses in Minnesota are working less than full-time. We also offer retention programs such as cash bonuses, tuition reimbursement, and other valuable perks. Our hospitals and health systems are constantly working on violence prevention, including providing ongoing, regular training for health care staff and refining security and incident response plans. MHA works directly with members to ensure better practices for workplace safety by developing a publicly available workplace violence prevention toolkit. As of December 2021, 100 percent of our members have completed the Preventing Violence in Health Care Gap Analysis. Minnesota’s hospitals and health systems want to ensure that their care spaces are places of healing and safety.

Carolyn: Nursing shortage cycles are exactly that --- cycles. We have had shortage and surplus cycles for decades, and probably for centuries. Notably, we haven’t had a pandemic strain in over a century, and we know the COVID-19 pandemic has definitely exacerbated our local, national, and global nursing shortage and will be a contributing factor for years. Additional societal factors that influence the nursing shortage, our work, and our workplaces particularly in critical high need areas are community and national economic challenges, racism, sexism, ageism, societal violence and unrest that bleeds into our nursing workplaces. Nurses continue to experience unacceptable rates of violence while they are doing their jobs despite awareness of the problem and risks.

How can employee recruitment and retention policies adapt to address the workforce shortage crisis?

JP:

Labor market competition is real and here to stay across practices and even industries, whether you’re talking about clinician poaching or clerical positions. Up and down the labor ladder, where I see folks being successful is on the margins - not in terms of game changing policies but incremental ones. Obviously pay helps move mountains, but that’s not really what I’m talking about. Flexibility and how when and where people work seems the single most critical thing these days. It is more complicated for those operating in clinical environments, but still a conversation worth having. In the space of governmental public health, this has become fairly paramount as so many folks have moved to the expectation of remote work, especially the younger generations who have a wide variety of employment options. Everybody is fairly used to remote work now, which has set a default expectation that will be hard to break going forward. The second major thing that employers can do is consider internal promotion trajectories without being what I’ll call ‘precious’ about the expectation that staff would stay with you forever, as previous generations have. What do promotions look like as incentives and rewards if you don’t expect staff to stay more than three to five to seven years? How can you use these strategically and tactically but also fairly? Because staff leave so frequently when they do not see promotion opportunities, this is critical. In small practice environments, I imagine this could be very challenging in some respects. In government, this is similarly challenging because there are often very few supervisory and management opportunities and a lot of frontline opportunities. Similarly, succession planning has become fairly important because of the large turnover among younger or short tenure staff and those planning to retire soon. Succession planning isn’t something that we talk about or are very planful about. Folks just leave and we lose that institutional knowledge. Maybe we should do better.

Retention is about pay, but not just pay..

—J.P. Leider

Tenbit: Investing in workforce by providing training to expand skillsets, focusing on development, mentorship programs and an equitable approach to promotions and growth opportunities all increase engagement and satisfaction in one’s career and should be a part of employee retention strategy. The ‘all hands-on deck’ approach to combating COVID-19 put all these efforts on the back burner. Given where we are today, a comprehensive employee retention strategy needs to be priority.

Jakub: Tuition reimbursement and loan repayment support can aid both recruitment and retention, as can providing benefits that address child and elder care tailored for the health care 24/7/365 workforce. Time flexibility, including part-time vs. full-time employment, is an important factor that could draw more people into the workforce.

Rahul: Just as hospitals and health systems adapt quickly to our environment and patients’ needs, so must our policies and tactics in the human resource space. We are seeing our members implement tactics such as social media, robust employee referral programs, and other out-of-the-box ideas focused on their missions to recruit the right individuals. We also see them find creative ways to retain their staff, such as bonuses and raises, to peer-to-peer support groups. It is an ever-changing world, and we know our members are doing all they can to retain and attract staff effectively.

Carolyn: As a nursing faculty member, I believe it is critical that academia take seriously the salary differentials that disincentivize nurses to consider being a nurse educator or nurse researcher. This is not a nursing discipline-specific challenge; it is well understood across disciplines that choosing academia typically translates into a lower compensation package as compared with an industry position. Historical justifications or explanations of this reality have included flexible work schedules, autonomy to pursue scholarship, job security for tenured positions, and benefits packages; these justifications have weakened over time and are not outweighing other factors, as evidenced by faculty shortages and some concerning faculty turnover trends persisting in schools of nursing. Practice-academic partnerships, joint appointments, and hybrid employment models are certainly possible mitigating solutions but require more investment, implementation, and evaluation. Furthermore, it is important these solutions do not simply add more work to already strained nurses in practice or in academia.

Lynda:

We’re passionate in our belief that the health care system must shift from “recruit and retain” to “attract and thrive.” It’s not enough to keep nurses from leaving – we need to reimagine workplaces that attract nurses to a great place to work and where they can flourish. The good news is that nurses are very communicative about what they want in their workplaces. In addition to safety and support, they are looking for career path opportunities, mentorship, and professional development. Nurses need to see the opportunities for growth and trust that their organization wants to see them advance and thrive. Additionally, innovative nurse leaders continue to develop exciting ways to embed flexibility into nurse staffing and scheduling, which has been a longstanding wish from the frontlines. From gig solutions to virtual options, to encouraging retired nurses to come back through flex scheduling, nurses in some health systems have more options than ever, and responsive health systems are figuring out how to work with these changing dynamics to improve nurse satisfaction and patient care. Health systems can also do more to build their workforce from their local communities, partnering with local elementary, junior and senior high schools, community colleges and universities to attract students into health care careers, and then offer a pathway to enhanced education and career development.

Nurses continue to experience unacceptable rates of violence while they are doing their jobs.

—Carolyn Porta

How does corporate leadership responsibility factor into the current crisis and how can it help address the issues?

Jakub:

Corporate leadership needs to be tireless in listening to caregivers and staff. Health care professionals want to be able to focus on patient care, not the bottom line, and they want to be respected as the experts in their fields. Operational decisions should include health care professionals to assess the impact both on caregivers and patients. Valuing health professionals’ input would go far to create better work culture and improve retention.

Lynda: A nursing shortage is a health care crisis for us all, and more awareness is needed surrounding what is happening and why, to build a pathway out. A health care system without enough nurses cannot function, and the economy cannot thrive without a healthy workforce. Provider shortages have plagued many rural and urban pockets for many years, and there is important work underway to resolve these care deserts, but it is also important to acknowledge that rising nursing vacancy rates will affect every kind of community in the years to come. Regardless of industry or region, the ability of the workforce to get care is essential. We need to work together, from the C-Suite to community to Capitol Hill and beyond, to build a health care system where nurses can grow and thrive, not just survive, to provide better care for their patients as well as themselves.

Carolyn: Leadership sets the tone of an enterprise. A direct supervisor is the primary reason why someone stays or leaves. Amazing leaders have figured this out, and everyone else really needs to. It is a more productive thought exercise to focus on the leaders and organizations who have done the best through the crisis up until now in supporting the health and well-being of their workforce. What are they doing that is contributing to their employees being committed to their work and workplace, despite difficult and tenuous work environments? What best practices could be learned from them and applied in the organizations that are most struggling with turnover, team dysfunction, and/or employee dissatisfaction or disengagement.

What are some of the barriers to health care industry job access and how might some of them be resolved?

JP: Governmental public health faces a number of the same challenges as the health care industry in the space of recruitment, plus the most challenging aspects of public sector hiring. Recruiting skilled, health-adjacent labor in this market is costly and highly competitive. If you’re looking for clinical providers, it seems that most everybody else is, too. If you’re looking for a data-savvy staffer, be prepared to compete with health care, non-profits, and tech. The challenge that public health faces in these regards is deepened by the fact that is fundamentally a public sector enterprise, and so suffers from antiquated hiring practices or timelines, HR information systems, and some odd hiring rules to boot; some places make applicants take civil service exams, for instance. One of the biggest things the health care industry, or governmental public health can do is to modernize hiring. Recognize that employers are competing for applicants as much or more than applicants for employers. Competitive compensation is important, but doesn’t mean a lot if it takes eight weeks to hire somebody when your competition is doing it in three weeks.

Tenbit: There are many primary care - family medicine and internal medicine- residency spots that go unfilled every year. Addressing the gap between salaries of primary care and specialty care providers and providing incentives for those who are willing to live and work in areas that have significant workforce shortage may alleviate some of the problem. The American Nurses Association reported that approximately 60,000 nursing applicants were turned away from nursing schools last year. We should explore the entry requirements and whether they make sense in today’s environment. So often, we have had requirements in place without critically examining if they are still applicable. The same could be stated for some jobs in health care. We should examine if people need to have a degree or certification prior to applying or if on-the-job training is applicable. These are the steps that will not only address the workforce shortage but also help us build a diverse workforce.

Carolyn: There are numerous barriers to pursuing nursing or advancing in nursing from entry level roles to advanced practice roles that must be addressed to adequately and efficiently overcome our current and predicted shortages.

Rahul: There are things that legislators can do right now to help address workforce challenges, such as supporting expansion of the loan forgiveness program. The Minnesota Nurses Assoociaion has suggested $5 million for nurses. MHA would support that but would also like to include other health care professionals who are critically important care team members. They could support additional mental health funding potentially with a grant program targeting the mental health needs of health care providers. In the short term, we are asking lawmakers to intervene before matters get even worse. We need loan forgiveness and scholarships for students in all areas of health care, including allied health professionals. We must make a significant investment to build the health care workforce pipeline, including programs for career laddering and exposing students to health care careers at an earlier age. We must accelerate entry into the professional workforce by simplifying administrative processes at the health care licensing boards.

Lynda: The road to a career in health care begins early. I would love to see greater reach into elementary and junior high schools to introduce careers in health care to students, ensuring that quality STEM education is accessible to all more widely and earlier – to ensure high school graduates are prepared to successfully enter and complete nursing or medical degree programs. Financial requirements can also be a significant barrier – this is where scholarships or loan repayment programs can play a role. Mentorship along the way is vital. Further, there is a bottleneck at the higher education level. A lack of nursing educators means 80,000 qualified prospective nursing students are being turned away each year. In other words, student capacity is limited exactly at the time we need more RNs. Health systems can also play a role by employing innovative staffing solutions, such as blended, team-based care models that bring together registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, certified nursing assistants, and patient care technicians to collaboratively care for patients as a team. These approaches create professional health care experiences for more prospective nurses and provide an entry point to the profession.

Jakub: Barriers like the costs of professional licensure or the time and cost of continuing education can discourage people from joining the health care workforce. Available need-based funding could relieve these issues, and virtual learning has provided flexibility for ongoing education. Immigrants with health care credentials from their home countries face significant obstacles including complicated applications and long waits. Simply centralizing the information on requirements for all health professionals would be a productive step.

What elements of how and where care is delivered could address workforce shortage issues?

Lynda: Nurses are absolutely transforming where care is delivered, increasing access, and improving outcomes. Virtual models – like those at Atrium Health in North Carolina and the Community Health Network in Indiana are allowing experienced nurses to virtually interact with patients and support care teams on the floor. Nurses are also advancing telehealth capabilities, providing access for patients who may otherwise be unable to receive care, such as those in shelters or rural communities. Nurses are also behind shifts to at-home care and retail health care, and in every example, the role and impact of nurses in community care grows, as does the scope of professional options and flexibility for nurses.

Jakub: In Minnesota a big issue has been the lack of pay/reimbursement for virtual visits. We learned through the pandemic that virtual visits—whether by phone or video technology—can be an effective way to deliver care and appeal to many patients. Having reimbursement for virtual visits could improve access for all Minnesotans, particularly those in communities that lack accessible health care nearby, particularly in mental health. We also learned during the pandemic that broadband is an essential community infrastructure that not only improves access to health care, but is beneficial and often necessary for employment and education. To ensure equitable access to virtual visits, we must also advocate for rural broadband access.

Rahul:

As many communities across Minnesota struggle to retain access to health care services amid growing caregiver shortages, telemedicine allows residents to receive care locally, makes care more convenient, extends the reach of otherwise scarce specialty services, and helps hold down rising health care costs for employers and individuals. Telehealth addresses some intense health care access gaps. However, as health care, we need to embrace newer professionals such as community health workers and programs such as hospital at home. These professions and innovative programs only help further address gaps in health care delivery. This is also an interesting time as we see a nexus of humans, technology, and artificial intelligence all entering the health care industry. Students and staff interested in technology and looking into this intersection will bring a plethora of new careers and ideas to deliver health care better. Despite all of that, there remains a lot of joy in caring for patients in person. As we continue to innovate with technology, we also must remember the value of in-person care in all patient care settings.

Corporate leadership needs to be tireless in listening to caregivers and staff.

—Jakub Tolar

Carolyn: Regarding the how, it is imperative that every health care professional is able to work at the top of their license and/or certification. This is critical yet continues in some health care settings to be strangely controversial. Creativity in health care delivery in the community is particularly critical, supporting individuals and families in their homes, focusing on screening and preventive efforts, and intervening early when indicated. This isn’t done by one discipline; this is a team effort and requires our creativity and collaboration. If we could achieve the goal of all of us functioning at the highest level of our license and doing so with appreciation for the critical contributions of all team members, then we would likely accomplish greater successful prevention of disease and illness, earlier intervention to prevent greater harms or sequelae including avoiding rehospitalization, and improved community-level health --- all of which would positively impact workforce needs and shortages.

JP: Telehealth is rightly on the minds of policymakers and practitioners as we think about shifting how and where care is delivered, but in public health one of the biggest shifts we are seeing right now actually occurred in health care decades ago - labor stratification in clinical delivery and support teams. Community health workers (CHWs) are becoming more common in health departments, and some are being hired to provide certain types of care that nurses used to provide in clinics at health departments. However, many are also going out into the community and connecting with the community outside of the four walls of the health departments. Admittedly, public health nurses have long done this as well. It has been a tenant of public health practice that nurses have done most every position and activity within a health department, but with CHWs more coming into the mix, nurses are starting to have the ability to focus more on their core areas, just as health care did so long ago.

What are ways your organization is leveraging technology to address workforce shortage concerns?

JP: As a research center, we tend to use technology a little bit differently than other organizations. We are all about leveraging datasets - administrative, commercial, you name it, to try and better understand the state of the workforce. There are some specialized products that scrape job posting databases like Indeed or Monster that we can perform research on, to see how many and what kind of jobs are being posted, with what kinds of qualifications for what kinds of salary. We also look at how many degrees are being conferred by whom over what periods of time, geospatially. That helps us understand emergent areas of shortage and surplus. Finally, an important area of understanding shortage is from workers themselves. Survey data is incredibly important in this regard. There are major surveys in public health, like the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey, the ASTHO Profile, or the NACCHO Profile, that help us to understand the state of the workforce, what total counts are of the workforce are across various occupations, and what worker perceptions are. This helps build generalized knowledge around intent to leave and job satisfaction, but also specific tools and opportunities for improving recruitment and retention.

Lynda: Administrative burden is an often-overlooked aspect of nursing practice that drives dissatisfaction and turnover. The rate of innovation in health care technology continues to accelerate, with increasing potential to free nurses from paperwork and other lower-skill tasks to focus on high-skill patient care. From scheduling and staffing solutions to portable patient monitors, electronic peer reviews and supply tracking systems, tech will be an important tool in the health system toolbox to best leverage nurses’ time.

Is there anything else about the health care workforce shortage crisis that you would like to discuss?

Lynda: It’s important to acknowledge that while COVID-19 exacerbated the current nursing shortage, the foundational pain points existed long before the pandemic. The first step to solving nursing’s challenges is seeking out, including nurses in the discussion and listening to their concerns and ideas for how to drive improvement. While nurses know what the challenges and opportunities are, nurses, integrated teams and senior leadership must come together to build truly meaningful solutions, leveraging measurable test-and-learn approaches, prioritizing and supporting the mental well-being of health workers and continuing to strengthen leadership and broaden overall skill sets, so that nurses are prepared, capable and energized to lead health care’s transformation.

JP: Last year the Star Tribune made waves when it published an article on the MDH report, “Minnesota’s Health Care Workforce: pandemic-provoked workforce exits, burnouts, and shortages” about how the rural health care workforce in our state is facing massive turnover. If you haven’t seen it, it’s an instructive read. Something like a quarter of the workforce says they are planning to retire in the next five years, or quit. We really need to do something about that. The thing that drives me crazy though about this report? Public health is above 40 perccent, and is not mentioned in the report or in the Star Tribune article. During a pandemic, it is not mentioned, even in the background section. Times are tough for health care organizations and public health organizations, and we definitely should not conflate the two. But when we are talking about workforce shortages, it is probably worth mentioning both and working on both together because of the labor market competition issues and because, during a pandemic and even into recovery, I’d argue that we need to focus on both. The solutions are different but the drivers are similar: everyone is facing stress and burnout, wants higher pay, and wants to be engaged more meaningfully in their work. In these ways, we are better together than apart.

Rahul: We are currently trying to work on the licensure process with the state licensing boards to expedite the licensing process in Minnesota. At the moment, it is a cumbersome, long, and inefficient process that delays our desperately needed talented workforce starting their positions. We are looking at legislation, and discussions with the board to create a more robust system.Finally, reminding the public that health care shortages are very real is crucial. We must work across sectors and with lawmakers to make significant investments. The question remains: “How can we inspire not just college students but younger students about the joys of a health care career?”

Carolyn:

Most of us are in health care, and health care higher education, because we believe we can be a source of good in some of the most challenging and difficult situations experienced by individuals, families, and communities. We have historically believed we can set aside our own life challenges and concerns and meet our patients, students, and colleagues where they are in that moment. But these last few years have brought us face to face with the finiteness of our capacity, individually and collectively. The shortage is simply a symptom and while it will likely persist for the near-term, my hope is that we can diagnose and address the underlying macro- and micro-conditions that contribute to our shortages.

MORE STORIES IN THIS ISSUE

cover story one

Health Care Utilization: Finding the right balance

By Zeke McKinney, MD, MHI, MPH

cover story two

A Missed Opportunity: The Prescription Drug Affordability Board