ospital at Home (HaH) is defined as a care management program designed to deliver acute care hospital services to medium acuity patients in their homes. While this model of care has been around for decades, there is recent growth in enthusiasm for its benefits. Its origins can be traced to the UK, Canada and Israel in the 1970s. In the United States, Johns Hopkins is credited for taking the first steps in 1995. They encountered barriers, however, with local payers, particularly state-based Blue Cross plans, who had no codes available for payment for acute care hospital services in the home.

cover story one

Hospital at Home

Inside a growing trend

By David W. Plocher, MD

In 2018 CMS produced its Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program now planned to conclude December 31, 2025. This bundled payment initiative, applied primarily to orthopedic and cardiac procedures, used a fixed episode payment for 60 to 90 days of care from the index surgery. The HaH relevance here is the following patient disposition predicament: “Reason for continued hospitalization is that there is nobody home.” Part of the mission of the BPCI as a risk bearing entity (RBE) was the highly pressurized challenge to reduce hospital stays. Post-acute providers became more valuable, with important exceptions.

On examination of that post-acute care segment, large payer databases showed that the acute care hospital trend (per member per month) was only 3%. The post-acute care segment trend was 10%. This appeared to be based on three sites of post-acute care: the subacute facility, the skilled nursing facility, and the hospital observation unit. Those sites had unit costs per day that were out of control with unit costs that were not well coded or benchmarked. In part this is because unit costs are difficult to control contractually. Of special interest is that the list of conditions deemed appropriate for observation units has evolved to be nearly identical to the conditions that could be served through HaH. A quick conversation with any hospital CFO will reveal a negative contribution margin, or ratio between profits and revenues, or DRGs such as pneumonia or heart failure. Root cause analyses show that facility labor expenses are cost prohibitive. Frankly, the hospital CFOs prefer not having a log jam of such patients on their floors and appreciate making room for more lucrative admits, such as hip replacements. Most CFOs hire consultants with engineering expertise for such throughput initiatives. A viable solution is managing these post-acute patients in their homes under the care of a high-tech home care provider, thus minimizing the unit cost per patient day. The RBE wins.

HaH patients have 32 % lower costs than similar patients using traditional hospital care.

Expanding the Concept

In March of 2020, CMS introduced its Hospitals Without Walls initiative, which in the face of public health emergencies (like COVID-19) allowed variance in health care facility standards. In November of 2020 CMS launched the Acute Hospital Care at Home Waiver (AHCaH), which allowed thousands of patients across 300 hospitals in 37 states to receive acute care in their homes and applied to 60 eligible conditions. Early impact suggests a superior discharge process since the patient is already at home. The care team has a direct line of sight into any social determinants of health (SDOH) issues. The initial uptake, however, has been slow: The largest HaH programs serve only 40 to 50 patients per day and, unfortunately, fewer than 50% of hospitals in the AHCaH waiver have reported a discharge under the program. Nevertheless, today, over 400 hospitals participate in the program and many project brisk growth.

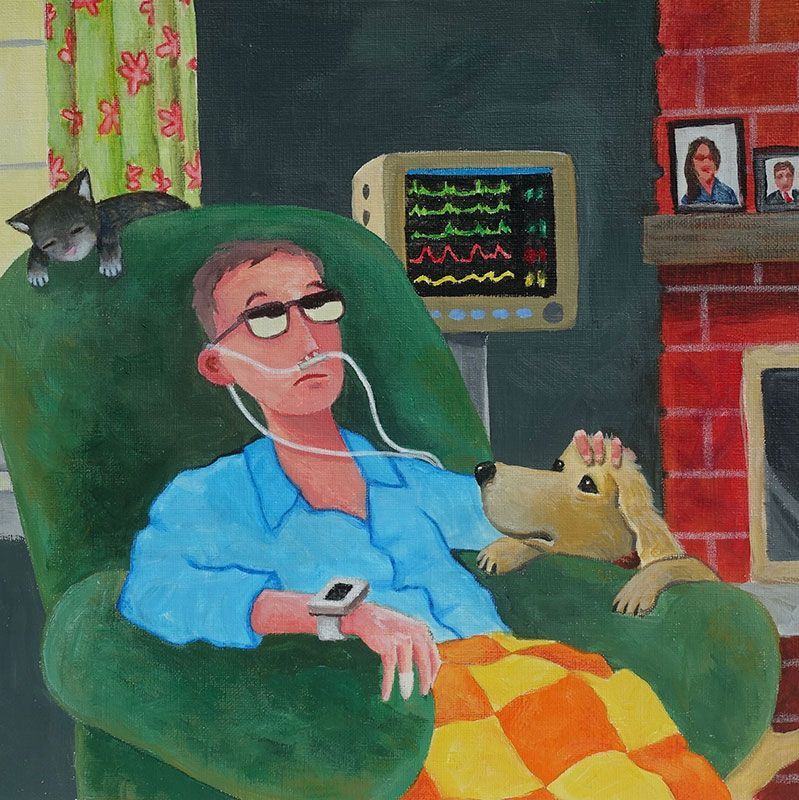

HaH workflow starts when a physician evaluates a patient for program eligibility while still an inpatient or in the ER. A staff person explains the program to the patient, answers questions, determines if the home environment can support the patient’s required services, obtains patient consent and assigns patient to a care team. Usually, the hospital supplies transportation for the patient to the home.

In the home, the on-site team, usually a mid-level provider and a nurse, visits the patient once or twice daily and remains on call 24/7. Initially, physician oversight is provided virtually. As determined by complexity or severity of illness and intensity of services, the physician might make home visits daily.

The patient can receive routine diagnostic testing such as ECG, echocardiogram, other ultrasounds, other imaging and blood testing. Therapies patients can receive include oxygen, intravenous fluids, intravenous antibiotics, routine medications, respiratory therapy, skilled nursing services and pharmacy consultation for medication therapy management. In addition, the patient can receive multiple remote monitoring services, usually integrated with the electronic health record, the most recent of which is the input of data from wearable devices. When discharge criteria are achieved, patient care is transferred back to the primary care physician.

Candidate Hospitals

The best candidates to provide HaH services are usually large health systems in metropolitan areas either operating a health plan or participating in value-based contracts or bundled payment contracts. They will have conducted a readiness assessment to quantify their internal capabilities for delivery, such as an internal audit that demonstrates capabilities comparing favorably to those in the requirements on the CMS web site for AHCaH.

If the index hospital, however, has a fee only for a service payer mix and no RBE track record with little infrastructure to support HaH, that hospital must conduct an environmental scan to find a mature HHC vendor who has an RBE track record and an HaH track record and is willing to partner. At that point they must consider a build versus buy analysis before making any outsourcing decisions and C-suite buy-in is critical.

When developing HaH services a good business plan will quantify the size of the applicable target market. For example, such an analysis may conclude that HaH programs are mainly viable in densely populated metropolitan areas. External expertise may help model the ideal number of daily visits needed by each team. Further external consultation is likely useful to show the expected market demand by service line.

There is ample literature and support for achieving HaH program goals and these fall into three main categories:

- Lower the total cost of care, especially as applicable to value-based care programs.

- Expand inpatient capacity, especially as applicable to fee-for-service business.

- Improve patient satisfaction and outcomes.

The best HAH patients are usually not catastrophically ill.

Within each goal, several other key performance indicators are typically developed. A rigorous proof of return on investment is pending necessary changes in coding and payment policies. The health system that approaches a payer for contract negotiation has, however, a business-case advantage when positioning its HaH program against other health systems lacking that total cost-of-care advantage. For example, there is public domain literature showing HaH patients have 32% lower costs than similar patients using traditional hospital care. Furthermore, the literature is replete with accounts of nosocomial infections from antibiotic-resistant bacteria as well as the very nature of such a medical-error prone environment. Then there is “sundowning” where the family visiting a loved one in the intensive care unit helplessly watches the patient have hallucinations.

Candidate patients

Several considerations that go into determining which patients are the best candidates for HaH care. A brief consideration of the leading ones start with age. Generally patients are over 65, as most of earlier comments on post-acute care services do not apply to the younger, commercially insured, population. Exceptions to this in European literature show some promise in pediatric patients. Payer mix becomes a concern as the HaH model is less applicable to the fee-for-service environment. Success is more likely in concert with a risk bearing entity, e.g., Medicare, Medicare Advantage, managed Medicaid and commercial-value-based contracting arrangements. Health status is important because the best HAH patients are usually not catastrophically ill. This is the intention of characterizing them as medium acuity. Out of the list of 60 conditions CMS recommends for HaH, most commonly found are urinary tract infections, pneumonia, heart failure, COPD exacerbation, diabetes and cellulitis. Again, note the overlap with conditions deemed suitable for the observation unit.

Two overarching characteristics of these conditions are that they can be safely managed in the home and their course is modifiable. Internet access is required for remote patient monitoring and complete communication. Access standards are applied that involve patient location, with a limit of 30 minutes transport time from home to hospital. An on-site assessment of the home must be conducted, which includes evaluation of a family member or trusted friend who is willing and able to become a trained participant in the patient’s care. Home-based care giver availability is critical to HaH success. Finally, and perhaps most critical, is having a primary care physician agreement. Each candidate patient assessment must be in collaboration with the patient’s primary care physician. The purpose is to find out if the patient’s physician is on board with the program. Many PCPs might prefer to simply hospitalize the patient where a nocturnist handles all care and the PCP’s phone doesn’t ring at 3 a.m. It is common for the PCP to ask, “How will this HaH program impact my daily workflow?” or more directly, “What’s in it for me?”.

Immediate Challenges

The biggest hurdle for HaH involves payment reform. This is especially uncertain as the waiver for the current HaH program is scheduled to expire in December 2024. It is imperative for Congress to act to fuel further investment. Making the existing waiver permanent would be ideal. A five-year extension, however, would pave the way for better certainty among regulators and lawmakers around the value HaH offers.

A surprising challenge lies in both patient and PCP preference for the conventional hospital level of care. Change management has become an important part of health care delivery and in this case change often relates to fear of being the first to fail. A better mousetrap may be difficult to perceive at first, and for many patients that is exactly what HaH can be. Workforce shortages involving RNs and mid-level practitioners, as well as PCPs, are currently a limiting factor and are being addressed by many state and federal initiatives. Ironically, HaH may itself be a part of the solution to these problems as it creates a specialized new area of health care delivery that could draw new individuals into the health care workforce. If there is the absence of a trainable home-based care giver, whether relative or family friend, HaH will not succeed.

Inherent in the development of this exciting new field of health care delivery are technological advances in diagnostic and monitoring equipment as well as in other medical supplies. Challenges around the logistics of timely home delivery of supplies, medication and equipment must be met seamlessly.

What’s Next

HaH presents the rare opportunity to actually reduce the cost of health care and improve both outcomes and the patient experience. Already a growing industry of new corporations offer HaH-in-a-box services to hospitals, and they will need to be managed, monitored and regulated. As with every innovation in health care, vigilance around unintended negative consequences must be integral. New pathways for messaging and care-management communications will be developed, and these may prove beneficial throughout all of health care delivery. When the new methods for coding and reimbursement are developed it is important that they are transparent to all parties. HaH has been described as a movement whose time has come. It is a well-researched concept and meets a growing need.

David W. Plocher, MD, has been a health plan chief medical officer and an international management consulting firm partner, working for hospitals and payers.

MORE STORIES IN THIS ISSUE

cover story one

Hospital at Home: Inside a growing trend

By David W. Plocher, MD

cover story two

Community First Services and Supports: A New Model for Personal Care Support